On a late summer evening when Johnie Bravo was just 4 years old, his owner Riley Kosirog took him for a leisurely trail ride near their home outside of Phoenix, Arizona. "John", who had only been under saddle for two months, seemed to be enjoying himself. But at the edge of a dry creek bed, John suddenly planted all four feet.

"It wasn't like he was balking or spooking," remembers Kosirog. "He just stopped and stood there. I put my leg on him, then shushed him to go forward. He blatantly ignored me."

Just a few seconds later, a thick, four-foot-long rattlesnake emerged from behind a boulder only a few feet away from where they stood. While Kosirog stared in shock, her mount calmly tracked the snake with his ears. As soon as the reptile had passed, John let out a sigh and continued on the trail toward home.

Since that day, John has alerted Kosirog to enough snakes and other hazards that she trusts her horse implicitly.

"If I'm riding with somebody who maybe hasn't seen a lot of snakes, and they're worried, I just say, 'we've got John'," Kosirog says with a laugh. "I have full faith that he won't let anything get by without letting somebody know."

John comes by his survival instincts naturally--he was born to a feral herd living near the Four Corners region of the Navajo Nation, and survived the area's harsh environment for nearly two years. Technically owned by the Nation but managed by no one, these feral equines live a hardscrabble life in the arid high desert, facing extreme cold in the winter and chronic drought in the scorching summer. It is not uncommon for the animals to be found dead along washes or near dried up mud puddles, victims of thirst and starvation.

Similar to BLM mustangs, Navajo Nation horses are not truly wild, but rather the descendants of domesticated horses turned loose to survive on their own. Some are former ranch horses or have experienced at least basic human handling; others, like John, are completely untouched. Periodically, some of the animals are gathered and sold.

Kosirog was a teenager when her boss acquired John after one of these gathers. A "scrawny, scruffy, underfed" long yearling, John bore a large, disfigured brand on his left flank, and tolerated people petting his head from the other side of the fence--but nothing more. Kosirog found herself drawn to the youngster, and whenever she had a spare minute, she sat on the fence and watched him. Slowly, the two began to trust each other, and later she helped him master basic handling skills such as leading, tying, and grooming. In 2018, Kosirog's boss sent John for formal under saddle training--then gifted John to her as a high school graduation present.

An enthusiast of many equestrian disciplines, Kosirog taught John to jump, and competed him in local jumper shows as well as at US Eventing Association horse trials. Wherever he went, the now well-muscled 14.3 hand powerhouse drew attention--most often due to his lofty, ground covering trot.

"Sometimes, it doesn't even look like he is touching the ground," says Kosirog. "He floats."

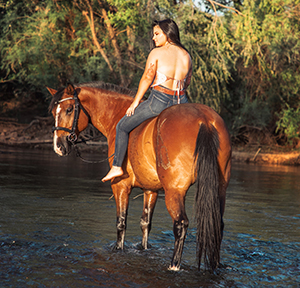

When John outgrew Kosirog's English saddle, she began riding him western instead. They continued to practice their dressage skills while also learning classic western moves like neck reining and the sliding stop. Most of the time, she rides him bitless, in a simple loping hackamore.

"We've had the past couple years to enjoy ourselves, and to continue training without any pressure that we have to get ready for the next horse show," says Kosirog. "We have just been growing up, together."

Kosirog believes that John is the perfect ambassador to show how much "grade" horses have to offer.

"You can have all the breeding lines in the book, and you can end up with a horse that doesn't want to do its job," says Kosirog. "I have no idea where John came from, or what other horses were out there on the range with him-- but out came this adorable, fancy moving, small horse."

More than once, Kosirog has been approached by people who assume her elegant moving mount must be a high-end import. She enjoys turning John to reveal his brand, and then explains his humble origins.

"I'll tell them he was a feral Navajo Nation horse, rounded up out of Chinle," says Kosirog proudly. "He is a horse that grew up drinking out of mud puddles, and eating sage brush. He lived enough to be able to end up being with me. And I can't imagine him anywhere else."